Fact Sheet

- Alignment of all storage processes with interval logic

- Storage location allocation matched to requirements

- Increased efficiency through process optimisation

- Optimised resource planning depending on demand

Optimisation of warehouse management in a fulfilment centre

With the global third-party logistics industry expected to surpass 2 trillion USD by 2030, third-party logistics providers have never had it better. Equally, their work has never been more complex. Ever-increasing customer expectations, supply chain entwinement, and stiff competition mean they need to be at the top of their game.

At the heart of any third-party logistics provider’s (3PLP) operation is the fulfilment centre. They come in all shapes and sizes, from local hubs handling a dozen or so customers and a few thousand items to the Amazon Fulfilment Centre in Dunfermline, measuring over fourteen football pitches in size.

On the face of it, the fulfilment centre’s role is simple: to store, pick, and make ready for delivery. Scale that up to potentially millions of individual items, however, and it quickly becomes a complex warehouse management task. Getting it wrong has consequences: costly inefficiencies impact profitability; missed SLAs incur contractual penalties; picking mistakes led to unhappy customers. In short, a poorly managed fulfilment centre hinders growth; it can even threaten survival.

A German fulfilment centre service provider faced exactly these problems. Having grown quickly, it lacked the maturity to handle its current volume and complexity. Picking times were too slow, missed delivery rates were too high, and mistakes had long since reached an unacceptable level. OCM were brought in to optimize the warehouse management and put the operation back on track.

In this article, we explain how we introduced a raft of new processes to achieve a fourfold improvement in on-time shipments and rescue the client from existential threat.

Background: Growth outstripping maturity of the fulfilment centre

Our client was a specialist fulfilment centre provider operating as part of a larger third-party logistics group. They offered a range of services to online shops, including goods receipt and storage, order picking, on-site packaging, and shipping to both B2B and B2C customers. Its warehouse was 20,000m2 and housed over 66,000 unique storage locations.

Like most logistics providers, our client had experienced an influx of business during Corona, with little time and too few resources to integrate the new volume in a forward-thinking and strategic manner. Legacy systems had long since been surpassed. Old ways of working went unquestioned. The staff were overworked and demoralised; in their words, 'nothing seems to change'.

Worst of all, promotional runs and the Christmas rush had caused a huge backlog of orders. More consignments left the warehouse late than they did on time. Customers were dissatisfied and were threatening to switch providers. The client had not increased prices in a while to keep customers onboard and the business afloat, but the operation was unprofitable. Everyone was losing out.

With survival at stake, the client had to improve its warehousing performance – and quickly.

Information Gathering and Analysis of Warehouse Management

As a first step, we undertook an on-site information-gathering exercise to determine the status quo and opportunities. This involved conducting workshops with a range of staff, including IT, customer service, sales, finance, and warehouse operatives. We also undertook a multi-day process evaluation exercise in the warehouse itself in the form of a time and motion study.

These two activities allowed us to form an anecdotal account of the challenges faced by the fulfilment centre and its staff, while also enabling us to map out activities on the warehouse floor and make our own evaluation of the client’s processes.

Alongside this, we undertook a comprehensive data-gathering exercise. Firstly, we reviewed the customer contracts, P&L statements, and price sheets. These gave us a picture of the profitability of the current business model and the constraints set by the agreements made with the customer and the wider logistics group.

More importantly, we interrogated the digital warehouse layouts and data from the warehouse management system, including invoices, goods receipts, warehouse actions, and anonymised operative data. With this, we were able to build a ‘Multi-Layer Path Model’. This model calculated the distance from any one point to another in the warehouse by sectioning and summing the distances between areas, rows and shelves. This allowed us to understand, in a quantitative manner, the efficiency of the current warehouse layout against a variety of improved scenarios.

An Ineffective Warehouse Layout and an Inefficient Flow of Goods in the Fulfilment Centre

The findings of our initial investigations on the warehouse management were as follows:

As a result of the influx of business and the bit-part manner in which volume had been added to the facility, a single client could be spread over multiple areas. This meant that pickers had to visit multiple locations for a single order. Furthermore, the clients were not placed with regards to access frequency, i.e. a client who experienced highly frequent orders could have been placed further from the picking access points than those clients who rarely received orders. This lengthened picking runs and wasted resource time.

We calculated that it took 23% longer to pick from a high or low shelf than it did from a mid-shelf; however, when the warehousing team organised a client area, the vertical position of an item wasn’t taken into account. Fast-moving items were only placed on the mid layer by chance, with many ending up on the top or bottom layer. Similarly, the fast-moving items were not placed at the end of the rows, where they could be accessed more quickly, another inefficiency.

The re-stocking settings for the warehouse management system had not been optimised or even questioned. As a result, the software often made incorrect or nonsensical suggestions. The restocking operative would therefore overwrite the software’s suggestions and restock to a different compartment. However, this action would lead to further inefficiencies, as the operative would make a restocking decision based on limited information and their ‘sense’ of what was right. For example, the operative would often restock to new compartments, rather than refill old ones. What followed was a chaotic goods layout. In some cases, there were up to 10 different compartments for a single item, blocking valuable compartments for other products.

When the inventory level of an item in the picking warehouse fell below one box, the inventory was, as standard, replenished with three boxes from the high-bay storage. For slow-moving items, three boxes were too much, leading to wasted space, and for fast-moving items, the re-order point was too late, leading to frequent stock-outs.

Teams and processes throughout the fulfilment centre acted independently, leading to inefficiencies. In particular, communication between the re-stocking and picking warehouse was ineffective; there was no consideration for the peaks and interdependencies of each other’s processes and needs. For example, while the pickers operated to customer SLAs, the re-stocking warehouse did not. As a result, pickers had to wait too long for the item to be replenished and consignments suffered delays.

The order picking runs themselves were inefficient and poorly planned, based on default software settings and a ‘gut feeling’. The pickers would begin their runs without waiting for enough orders to accumulate. This meant that the picking software could not form efficient, multi-order picking runs. The pickers would return with half-filled carts and return quickly for another inefficient run. This put time-consuming extra miles into the legs of the picking operatives.

Like all logistics operations, the fulfilment centre experienced peaks and troughs in demand. Peaks occurred on short timescales, for example in the hours before shipment cut-off time, and seasonal timescales, for example, the Christmas rush. The client did not flex its employee scheduling to meet these peaks. All employees would begin at the start of the day, when often there was less to do, leaving a scant operation for an end-of-day scramble. During the peak seasons, operatives stuck to their rigid hours and would book annual leave all at the same time. The warehouse would be shorthanded in a time of need. The order backlogs mounted and could not be reduced.

Optimisation of the Warehouse Management

Having collated the findings, we devised several initiatives to optimize the warehouse management in the fulfilment centre, improve performance, and, ultimately, retain the client’s customers.

Optimisation of client area distribution:

Using our Multi-Layer Path Model, we were able to perform a cost-benefit analysis of various warehouse layouts. This allowed us to arrange and optimise the distribution of the client areas in an informed manner. We consolidated clients into single areas or multiple areas next to each other so that warehouse operatives would no longer have to cross the warehouse for orders from a single client. We also placed important, high-frequency clients beside the picking access areas so order picking runs would be shorter for more frequently accessed clients.

Improved compartment selection:

We categorised products as slow-moving or fast-moving. We then introduced a regime whereby fast-moving items would be placed on the mid shelves, where picking is quickest, and the slow-moving items would be placed at the top or the lowest level, where picking takes significantly longer. Item size also became a determining factor for compartment selection: small items, such as headphones and textiles, would no longer be placed in large compartments, where they failed to fill up the space. Additionally, items that were often ordered together were placed in compartments next or near to each other to reduce the required movements of the pickers.

Improved re-stocking processes:

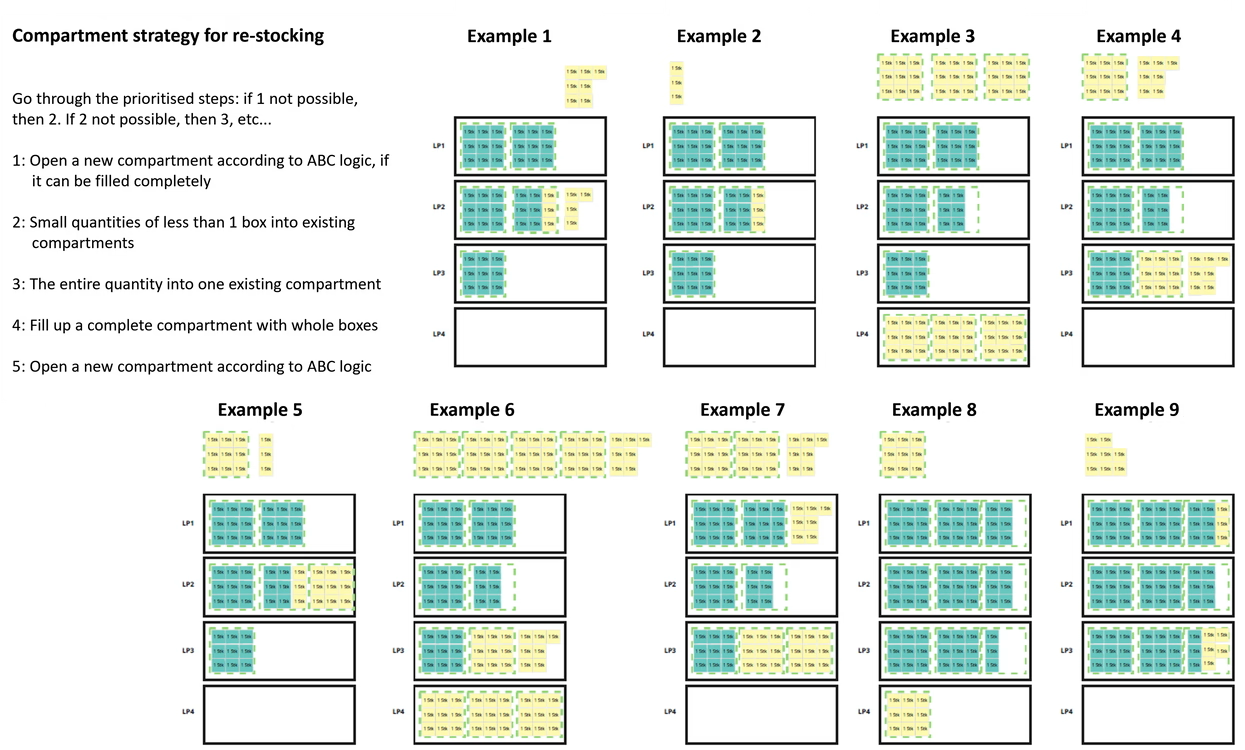

We devised new settings for the re-stocking software that would recommend the optimum compartment to re-stock to. The respective logic is shown in the picture below. New compartments were used only where necessary, otherwise additional quantities were added to already existing compartments. With improved confidence in the software, we were able to oblige the re-stocking operatives to follow its recommendations – no more overwriting of the suggested compartments. Additionally, the pickers had to prioritise picking from the emptiest compartments. This acted as a 'self-cleansing' system, clearing out the half-filled compartments and freeing up warehouse space.

Improved re-stocking parameters:

Based on historical data, we calculated two things: the re-order point for each item and the re-order quantity for each item. As a result, compartments for slow-moving items did not become needlessly over-filled, while for fast-moving items, there was now enough time to replenish the stock before a stock outage occurred. In addition, more than three boxes were res-stocked for fast-moving items, so that replenishment was needed no more than once a day.

Introduction of ‘batch’ picking runs:

Whereas previously picking runs would operate continuously and be routed by ‘gut feeling’ we created a ‘batch’ regime, whereby particular runs would take place every 1-5 hours, depending on requirements. Due to respective adjustments in the software, orders accumulated so that visits to specific sections of the warehouse would be worthwhile, resulting in filled carts and, overall, shorter picking runs.

Trolley-size optimisation:

To make the most of the new ‘batch’ order picking runs, we adjusted some of the picking trolleys from 9 compartments to 12 compartments. This was based on the order characteristics of the customer. For example, the second largest customer was a B2C business, which had smaller orders and was therefore better suited to trolleys with more separate compartments. This meant more orders could be picked on a single run, improving the efficiency of a picking run.

Hardware optimisation:

What might seem a trivial point, but one that in practice caused endless frustration and delays, was the operation of the hardware, such as printers and scanners, which were previously overburdened and slow. Updates to the software and APIs made the hardware run more efficiently, improving label and documentation printing times.

Intervals for integration of processes:

Having mapped out the entire warehouse process, we were able to determine all the points on the critical path to an order shipment. This included specific timings, such as when orders were loaded onto the system, when restocking started, and when picking runs were formed and executed. Combining this information with contractual SLAs and carrier pick-up times, we devised a new routine that coordinated these processes and timings in intervals, resulting in shorter waiting times and higher efficiency. A major enabler of this coordination was the change to ‘batch’ picking runs. This provided singular points of alignment, computation, and planning, instead of continuous (and often inaccurate) calculation and recalculation.

Optimised resource scheduling:

We introduced new work schedules to address the peaks and troughs throughout the day. If there was less to do, employee start times would be staggered, so more operatives would be on duty for the shipment cut-off time and its aftermath. Flexitime and time accounts allowed the client to address seasonal peaks with internal staff. Additionally, a new set of vacation rules – for example, a maximum proportion of operatives on leave at any one time before Christmas – meant that the fulfilment centre wouldn’t find itself suddenly shortstaffed in a time of need.

Results of the improved warehouse management

Implementation of the above initiatives resulted in significant improvements in efficiency, the highlights of which are shown below.

- The new warehouse layout led to a 17% reduction in picking times

- The intervalisation of the restocking processes led to a 20% reduction in picking warehouse stock-outs

- At the beginning of the project, the % of on-time positions was just 15%. By the end of the project, on-time positions had improved fourfold to 60%

- Items delivered ‘over 3 days late’ reduced from 55% to 2,5%

These efficiencies, among others, resulted in over 400k EUR in annual savings, broken down as follows:

- Through warehouse configuration optimisation (such as client area optimisation), we realised 120K EUR in annual saving

- Through process efficiency improvements (such as picker routing, loading time reduction and hardware improvements), we realised 127k EUR in annual savings

- Through compartment allocation and replenishment improvements, we realised 190k EUR in annual savings

We also devised further initiatives for the client related to one of its key pain points: price determination. With its newly improved performance, the client could begin to restore its reputation and increase pricing back towards the industry standard. But it wasn’t just a case of asking for more money.

Firstly, the client had to demonstrate to its customers that its performance had improved. We recommended a number of new data management measures and enhanced KPIs so the client could prove that it was meeting, or even exceeding, its contractual SLAs.

Secondly, we recommended a data-driven price negotiation regime. Rather than entering the negotiations with their backs to the wall and submitting to the customer’s demands, the client could enter negotiations with evidence-based assertions that would justify its prices.

We estimated the resultant annual revenue increase to be over 1 million EUR.

Optimisation of a Fulfilment Centre: Final Thoughts

Inefficient warehouse allocation, overlong picking routes, missed delivery slots: Our client was operating a sub-optimal fulfilment centre and facing drastic consequences.

Through detailed shop floor and data analysis, OCM identified the root causes of the issues and implemented practical solutions. Efficiencies followed, along with substantial financial savings.

OCM offer a range of logistics consulting services, including warehouse optimisation, logistics optimisation, and more. If your operation is facing similar difficulties and you are interested in how we might be able to help, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.

Logistics optimisation & Supply Chain Consulting modules

Logistics & SCM Opportunity Assessment

- Benchmarking & maturity testing

- Identification of opportunities & action plan

Transport Partner Management

- Transport partner strategy & professionalisation

- Securing resources and resource training design

Transport Tender

- Competition, effective transport tendering, fact-based negotiation

- Transport cost reduction

Freight & Logistics Tender

- Competitive pricing, quality, and performance assurance

- Individual weight-distance matrix

Warehouse Optimisation

- Efficient warehouse logistics & layout

- Optimised processes & working capital

Logistics Cooperation

- Optimising logistics through synergies

- Finding a fair and stable collaboration model

Route Optimisation

- Distance and route reduction

- Reduce resource & logistics costs

Supply Chain Network Optimisation

- Optimise delivery times, service levels, & processes

- Reduce working capital

Inventory & Order Management

- Optimal order quantity & stock on hand

- Optimise working capital

Fleet Optimisation

- Fleet concept tailored to requirements

- Cost optimisation

Supply Chain & Logistics Strategy

- Sustainable maximum value contribution of the supply chain

- Clear objectives, concrete measures

Digital Logistics Management & Reporting

- Information advantages in speed, scope, & significance

- Efficiency through automation, data integration & process simplification

Interim Supply Chain & Logistics Manager

- Rapid response: candidates within 48h

- Matching of requirements and assessment of suitability using logistics experts

- From dispatcher to logistics manager

Short-term staff shortage? Unexpected need for action?

Learn more